The road to reading

Reading is fun. It’s also a key skill that helps us to learn and to live our lives – so starting to read is an

In July 2021, DfE published The reading framework: Teaching the foundations of literacy which, it says, focuses on the early stages of teaching reading and the contribution of talk, stories and systematic synthetic phonics (SSP); supports primary school leaders to evaluate their teaching of early reading and best practice for improving early reading (especially in Reception and Year 1); and older pupils who have not yet mastered the foundations of reading. Reading the document for myself, a number of issues emerged from the guidance:

Below I discuss in more detail some concerns with the guidance, and make suggestions of additional issues to consider relating to the teaching of reading in Reception and Year 1.

Approaches to literacy education are underpinned by particular ways of conceptualising reading and writing in terms of what reading and writing actually are, and by particular ways of conceptualising how reading and writing can be learned. This document is a prime example of this where reading is conceptualised as the accurate decoding of text to read conventional words; and writing as the use of accurately reproduced conventional text to convey written meaning, ie conventional reading and writing. If reading and writing are conceptualised in this way, it therefore follows that literacy policy, curricula and pedagogy will involve adult conceptualisations of how best to teach children to do this. This is what this document is attempting to do through its “how-to” strategies for teachers.

The teaching of writing within the document is rooted in a fundamental assumption that it can only be developed as the result of age-appropriate, systematic school instruction; thus negating any recognition of children writing independently before this point, and incorporating a notion of writing as only being writing when it is formed of conventional text. It is important to additionally make a distinction between writing and handwriting. In England, children are taught handwriting skills from the age of six years in Year 1. Handwriting is however different from writing in that handwriting practice involves children learning how to form a fluent writing style through being taught effective ways to reproduce letters; in other words, the graphic symbols that represent the English alphabet. This is distinct from using writing as a means of producing meaningful communication.

It is a major omission that the guidance makes no mention of beginner reader behaviour or practice, or building on skills established in the EYFS.

From about 30 months onwards, most children are at the stage of role play reading. In this phase they are readers in so far as they show an interest in books and the print they see around them. They may recognize environmental print; the sign for a fast food outlet for example, or the logo on a supermarket shopping bag. They imitate the things they see adult readers doing such as holding a book, a magazine, or a newspaper carefully (although they may not hold it the right way around!), turning the pages, and sometimes providing a narrative as they do so. They often retell stories they have heard as they ‘pretend’ to read. They may read to their cuddly toys, dolls, friends, or younger siblings. It is important to develop children’s confidence in themselves as readers and there are several ways that they can be supported and encouraged to develop their early reading skills. The main goal is to instil a love of books and reading. In order to develop and consolidate their reading skills, beginner readers need to be treated as readers from the outset; to see reading as part of everyday life; to have access to a wide variety of resources and activities to encourage, develop and support their interest in print and their reading skills; be encouraged to join in with texts and read too; to see that reading is enjoyable and purposeful. Children who are more interested in reading will make use of the opportunities and experiences that are offered to them such as play-based reading opportunities that are grounded in meaningful contexts, constancy and consistency in terms of opportunities and situations in which to develop their reading skill, and to participate in an environment rich in reading opportunities (Bradford, in Palaiologou 2020:.256-7). Decodable texts are therefore insufficient on their own for learning to read.

Children learn to write conventionally over a period of time, usually years. Two main elements underpin the development of writing; first, writing skills development (the development of fine motor skills including hand-eye coordination and the physical ability to successfully manipulate a chosen writing tool); and second, compositional skills development (the cognitive processes involved in understanding and applying organisational elements such as genre, grammar and spelling to effectively communicate meaning). Children begin to explore the features of writing from a very early age. They do so with the intention of creating meaning before understanding of the alphabetic principle has developed, and despite the fact that the writing produced is not conventional in that it cannot be read by an adult (Bradford and Wyse, 2010; 2013, Bradford, in Palaiologou, 2020: 260).

Bearing these points in mind, the following areas of the guidance may need to be reconsidered:

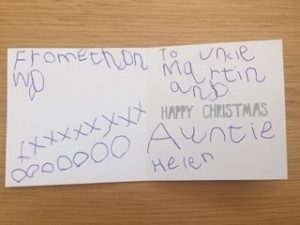

Note Ethan’s attention to detail! How he conveys his (very meaningful) message. What he already knows about writing a Christmas card. Think about how much more Ethan learnt about writing that afternoon! Intrinsic motivation to write is critical in the overall trajectory of a child’s writing development. How will dictation, where he is required to write what he is told to, help him in his future life?

While there are also helpful aspects to this document – such as the continued importance of phonics after KS1 in relation to spelling – it does need to be used with caution. Teachers need to retain confidence in what they are already getting right in the teaching of reading, in the great strides that have been made in the teaching of phonics since 2006 and the Rose Review. Most importantly, they must not feel professionally undermined by the content.

Helen Bradford is a freelance early years consultant and an Early Education Associate

Reference

Palaiologou, I. (2021). The early years foundation stage theory and practice. 4th Ed. London: Sage.

Reading is fun. It’s also a key skill that helps us to learn and to live our lives – so starting to read is an

What is mark making? Mark making is the term used to describe the marks that children in their early years make on paper and is

The power of picture books How wonderful it is to enjoy children’s picture books and escape into their imaginative worlds reading them aloud with children.

References and resources about cursive and joined up handwriting On our Cursive and joined up writing are not in the EYFS and Cursive and joined up writing in early

Cursive or joined up writing in the early years We already know that there is no mention of handwriting, joined up or cursive writing styles

Content published on 24.3.17 – not updated with references to the EYFS 2021 although the principles still apply Is joined up or cursive writing in

The three pages in this section help to present the evidence for NOT teaching cursive or joined up writing in the early years. The EYFS

Early Education

2 Victoria Square

St Albans

AL1 3TF

T: 01727 884925

E: office@early-education.org.uk