Letter to the next Prime Minister

The letter below sets out our key asks for the next government.

Most educators will be aware that “what works” in support of children’s learning and development is the subject of seemingly endless debate, with the role of play in education one of a number of hotly-contested points. It is not unusual to hear both researchers and practitioners writing off the educational benefits of play as largely trivial. Of course, play can be valuable in other ways; but as a route to improving young children’s academic knowledge and skills in key areas like numeracy, reading, and writing – is it really of much use?

One mistake we often make in our efforts to answer this question is to casually assume that play is a single homogenous concept. In fact, researchers are now beginning to address the fact that there are different ways that children can learn through play. In a recent study, we looked at a particular approach called “guided play”. Our results show that this playful approach to learning can be just as effective as traditional adult-led instruction in developing young children’s foundational skills. Furthermore, there is some evidence children may acquire certain skills – including maths – more effectively through guided play.

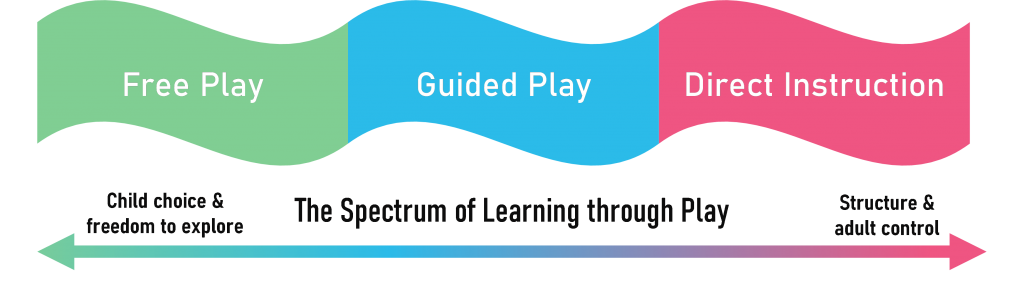

It’s useful to imagine play as existing along a spectrum reflecting different levels of child autonomy relative to adult control. At one end is direct instruction: formal, traditional teaching in which teachers present information to children or tell them what to do. At the other is free play, where children decide what to do with minimal adult involvement. This natural, self-directed play is what many of us might have in mind when we talk about play.

Guided play falls in between and describes playful activities that are scaffolded around a learning goal but allow children to try things out for themselves. Specifically, it has three characteristics:

There are all sorts of ways that you can set up a guided play activity, which many early years practitioners may find familiar. Imagine, for example, getting children to roleplay being in a shop and introducing the use of counting skills using toy money, or by asking them find a certain number of items to put in their shopping basket. Construction play is another good example, and typically involves children building structures using blocks and shapes, helping them practice their spatial thinking skills or learn target words about shapes and space.

Guided play has rarely been studied in its own right, so to understand its impact on learning, we identified 39 studies which captured information about its value compared either with free play or direct instruction.

Our analysis first identified studies which assessed guided play’s impact on similar types of learning outcome – for example specific cognitive skills, or certain aspects of literacy. We then calculated the overall effect size of guided play – positive or negative – compared with other approaches.

These effect sizes were measured using Hedge’s g – a statistical system that is widely used for such comparisons. Under this system, a value of 0 would mean there was no real difference between the impact of guided play and direct instruction. A small, positive effect would be signalled by a result of about 0.2; and medium and large effects would be represented by 0.5 and 0.8, respectively. If guided play turned out to be less effective than more traditional approaches, we would expect to see a negative reading instead.

In fact, our investigation into the impact of guided play on a range of key skills – literacy, numeracy, socioemotional skills and executive functions (a cluster of key thinking skills) – produced no statistically significant negative results compared with direct instruction. In other words: guided play tends to, at the very least, produce roughly the same benefits as more traditional teaching.

The effect size also indicated that guided play may be more effective than direct instruction, in developing some areas of maths. For example, guided play’s comparative effect size on early maths skills was 0.24, and on shape knowledge it was 0.63. One reason for this may be that some of the key characteristics of guided play – gentle prompting, keeping children on track, and allowing them time and space to figure things out for themselves – are particularly well-suited for helping them to master the series of logical steps common in maths tasks.

What does this mean for the debate about play and learning? Another important finding in our study was that there is lots of variation within guided play itself. Some of the guided play examples captured in the studies we looked at were closer to free play; others were closer to direct instruction. This indicates that there is no single rule about how to do guided play. As with anything else in education, there is a need to adapt to individual needs and wider circumstances, and it would certainly be wrong to suggest that play is always preferable to adult-led teaching.

In general, we need to understand more about how, when, and why guided play might work best, or for whom. It’s possible, for example, that it may influence other characteristics which have a positive, knock-on effect on educational progress – for example, by enhancing children’s motivation, persistence, creativity, or confidence in a learning environment. If we can understand more about this, we should be able to identify more precisely how it could be used profitably in educational settings.

Still, there is clearly a growing body of evidence that playful approaches to learning are more beneficial than is sometimes presumed. Particularly at the moment, when we are concerned about ensuring children catch up on learning “lost” during the pandemic, it would be easy to fall back on that casual conception of all play as “free” play, with limited results for skills acquisition. In fact, we should respect, protect, and value opportunities to engage children in learning through play. Coupled with support from a skilled adult, it appears to have real positive results for their education.

Read the research review: Kayleigh Skene, Christine M. O’Farrelly, Elizabeth M. Byrne, Natalie Kirby, Eloise C. Stevens and Paul G. Ramchandani (2022) Can guidance during play enhance children’s learning and development in educational contexts? A systematic review and meta-analysis, Child Development.

The letter below sets out our key asks for the next government.

Clare Devlin, Early Education Associate What aspects of physical development should we focus on within the Early Years Foundation Stage (EYFS) and other early years

by Anni McTavish What are treasure baskets? “Treasure Baskets” are a collection of ordinary household objects, that are chosen to offer variety and fascination for

by Debi Keyte- Hartland The term “Loose Parts” was coined by Simon Nicholson, a British architect and designer whose parents were artists Barbara Hepworth and

by Helen J Williams Early mathematics is essential for children’s full development, it is also predictive of later, wider achievement. Early mathematical learning is critical

by Kathryn Solly The benefits of outdoor learning in the early years have now been firmly recognised for both educators and young children’s learning and

What is continuous provision in EYFS? By Ben White Continuous provision in EYFS refers to the resources and learning opportunities accessible to children all of

The Families’ Access to Nature Project was undertaken by the Froebel Trust and Early Education between October 2021 and January 2022. Children, their parents, and

by Leslie Patterson At the very beginning of the 1970s I was lucky enough to attend a playschool, at a time when there was very

Guest blog by Sara Knight Why are opportunities for risk and adventure essential for normal development in the early years? Tim Gill (2007) identifies four

Why go outside? Big movers Have you ever been in an open space with young children? The first thing they want to do is to

Taking care of a baby is tiring work, with a lot of feeding, nappies and broken nights. When you are exhausted, it can be harder

Here are some links to resources to support your play. Loose parts play tookit is such a rich and comprehensive free publication from Inspiring Scotland to

When writing our January Early Years Teaching News, I tweeted a survey to ask if practitioners and leaders would like information about ICT or outside

This content by Jan White comes from our out of print leaflet “The Sky is the Limit: Babies and Toddlers Outdoors: developing thinking, provision and practice”

Healthy settling for high wellbeing How can we best help children feel at ease so that they are secure and settled in their new provision?

Early Education

2 Victoria Square

St Albans

AL1 3TF

T: 01727 884925

E: office@early-education.org.uk